|

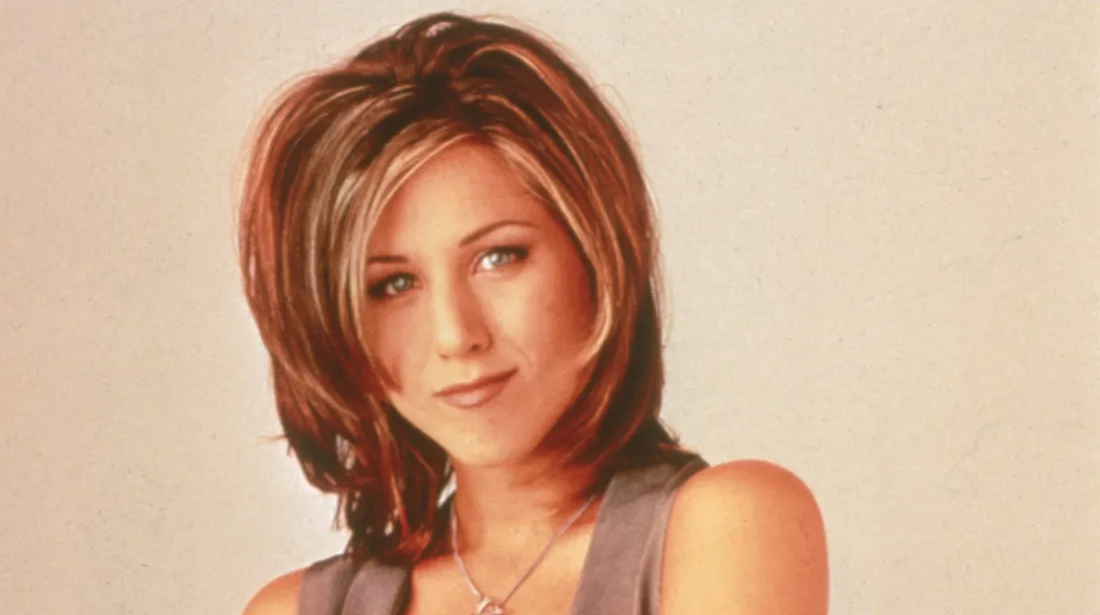

4/29/2021 0 Comments The Story of Hair: The One Where Jennifer Aniston's 'Rachel' Haircut on Friends Became a PhenomenonThe legacy of NBC's Friends isn't one of ratings records or piles of awards—it's about the way the show managed to impact popular culture by showing life at its most mundane. This is a series that turned sipping coffee into an art form, still prompts philosophical debates over the morality of being "on a break," and made it impossible not to shout pivot! when moving furniture. But Friends reached its cultural zenith when it managed to transform a simple hairstyle into a global talking point, as untold millions of women in the ‘90s flocked to salons all wanting one thing: “The Rachel.” “The Rachel” hairstyle, which was the creation of stylist Chris McMillan, was first worn by Jennifer Aniston’s Friends character Rachel Green in the April 1995 episode “The One With the Evil Orthodontist." It has its roots as a shag cut, layered and highlighted to TV perfection. It may have been a bit too Hollywood-looking for a twenty-something working for tips, but it fit in the world of Friends, where spacious Manhattan apartments could easily be afforded by waitresses and struggling actors. The Birth of "The Rachel" Aniston in 1996, during the height of the style. The style itself wasn’t designed to grab headlines; McMillan simply gave Aniston this new look to be “a bit different,” as he later told The Telegraph. In hindsight, the ingredients for a style trend were all there: The cut was seen on the show’s breakout star as the series hit its ratings peak; an average of more than 25 million viewers tuned in each week during Friends's first three seasons. You can’t have that many eyeballs on you without fans wanting to get closer to you, and the easiest way to do that is to copy your style. During the show’s second and third seasons in the mid-1990s, stories began to appear in newspapers and magazines about salons from Los Angeles to New York City and (literally) everywhere in-between being inundated with requests for Aniston's haircut. Some women would come in with their copy of TV Guide in hand for reference; others would record an episode of the show and play it at the salon to ensure accuracy. For these stylists, a good hair day for Rachel on a Thursday night meant big business over the weekend. "That show has made us a bunch of money," Lisa Pressley, an Alabama hairstylist, said back in 1996. Pressley was giving around four "Rachels" per week to women ages 13 to 30, and she was touching up even more than that. Another hairdresser estimated that, during that time, 40 percent of her business from female clients came from the "Rachel." During the early days of the trend, McMillan even had people flying to his Los Angeles salon to get the hairdo from the man himself—a service that he charged a modest $60 for at the time. A Finicky 'Do What many clients learned, though, was that unless you had a trained stylist at your side, “The Rachel” required some real maintenance. "People don't realize the style is set by her hairdresser," stylist Trevor Tobin told The Kansas City Star in 1995. “She doesn't just wake up, blow it dry, and it just turns out like that." That was a warning Aniston knew all too well. In recent years, she has expressed her frustration at not being able to do the style on her own; to get it just right, she needed McMillan on hand to go through painstaking styling before shoots. In addition to being impossible to maintain, in a 2011 Allure interview, Aniston called it the “ugliest haircut I've ever seen." In 2015, the actress told Glamour that she found the look itself “cringey." Though Aniston had grown to loathe the look, it was soon the 1990s' go-to style for other stars like Meg Ryan and Tyra Banks and later adopted by actresses and musicians like Kelly Clarkson and Jessica Alba. Debra Messing had an ill-fated run-in with it when she was told to mimic the style for her role on Will & Grace. They soon realized that trying it without McMillan was a fool’s errand. “[It] was a whole debacle when we tried to do it on the show,” Messing recalled. “They literally tried for three hours to straighten my hair like [Aniston's]. It was so full and poofy that it looked like a mushroom.” A Style That Sticks Around Aniston’s personal preference for longer hair soon made its way on-screen, replacing the shorter, choppier “Rachel” by season 4. The once-iconic look was officially ditched, the last remnants of which were washed away in a flowing sea of ever-growing locks doused in blonde, pin-straight highlights. And once a haircut’s namesake turns their back on the style, it’s likely only a matter of time before the rest of the world moves on, too, right? Wrong. “The Rachel” endured. Unlike Farrah Fawcett’s showstopping feathered hair from the ‘70s, celebrities, news anchors, and the average salon-goer were still wearing the hairstyle well into the 2000s. Even now, fashion websites will run the occasional “Is ‘The Rachel’ Making a Comeback?” article, complete with the latest Hollywood star to sport the familiar shag. It’s a testament to McMillan’s skill, Aniston’s charm, and Friends’s cultural sway over audiences that people are still discussing, and donning, the hairstyle some 25 years later. And in a lot of ways, the haircut's success mimicked the show's: it spawned plenty of imitators, but no one could outdo the original. From MentalFloss

0 Comments

Like stereotypes about any group of people, it should come as no surprise that many of the weird rumors and legends about redheads aren't always true. These are just some of the most popular ginger myths and why they just don't hold any water. Surely you've heard the myth that all redheads have not just a short fuse but also a fiery temper. Or perhaps you think that they tend to be bolder and brasher in general and are quick to act on their impulses. After all, the color red is often associated with strong emotions like passion hence the red boxes of candy that litter the shelves every Valentine's Day. But the reality is that redheads are inherently no more prone to explosive anger or even curt crankiness than anyone else. They are unfortunately more susceptible than others to being bullied, according to the BBC, so perhaps there's some psychology at work that reinforces the stereotype constant bullying certainly can have an impact on victims. But there are some other interesting factors at work here. Redheads do produce more adrenaline than others, according to Red: A History of the Redhead by Jacky Colliss Harvey, which means they, quote, "fire up more rapidly than others." If gingers are more prone to possessing a fiery temper, as the stereotype suggests, they must also be a hot mess in emergency situations right? All of that adrenaline rushing in will no doubt make them lose their minds and start freaking out about the situation as opposed to keeping calm and getting through it. Actually, that couldn't be further from the truth. That's because not only do gingers produce more adrenaline in general, but they also can access it faster than blondes or brunettes, according to Red: A History of the Redhead. And because they can synthesize the hormone more quickly, that makes them more adept in fight-or-flight scenarios. So they'd definitely have a head start while being chased by a bear or getting away from some bad dudes while you straggle behind them. So when you're assembling your survival squad for the zombie apocalypse, be sure to include a ginger or two, they just might save your life! Watch the video to learn more myths about redheads you always thought were true! The Chemistry of Redheads History has dealt a mixed hand to the redhead. Alternatively admired or derided for the color of their crowning glory, attitudes to those with red hair have always been polarized. Throughout time, redheads have been portrayed as beautiful and brave or else promiscuous, wild, hot-tempered, violent or immoral. Gingernut, carrot top, flame-haired, copper head and rusty just some of the nicknames for red hair. The modern mind also associates the hair color with individual countries such as Scotland and Ireland or cultures such as the Vikings. The reason for these attitudes and associations is complicated and lies partly in the origins of red hair and the human reaction to things that are different. For although 40% of people carry the gene for red hair, real redheads are rare, amounting to no more than 1% of the population. It requires two carriers to make a red headed child. So why is red hair so rare and unique? What is its history, and is it fair to assigned heads such a turbulent reputation? All in the Genes Red hair has always been a question of genes. Clues suggested that red hair could have evolved in Paleolithic Europe amongst the Neanderthals. Scientists analyzed Neanderthal remains from Croatia and found a gene that resulted in red hair. However, the gene that causes red hair in modern humans is not the same as that in Neanderthals. Nor is the red-haired gene of either race found in any of the peoples who are descended from Paleolithic humans, namely the Finnish and most of Eastern Europe. This fact not only rules out interbreeding as a route for Homo sapiens red hair, but it also rules out early Europe, as it’s the birthplace. Instead, the origins of red hair have been traced back to the Steppes of Central Asia as much as 100,000 years ago. The haplogroup of modern redheads indicates that their earliest ancestors migrated to the steppes from the Middle East because of the rise of herding during the Neolithic revolution. The Steppes were the perfect grazing lands for the herds of the agriculturists. Unfortunately, however, the lower UV levels of the area limited their bodies’ ability to synthesize vitamin D. Vitamin D deficiencies bring about weak bones, muscle pain and rickets in children. So the migrants had to change. To survive their environment, people living in northern regions, in general, had begun to evolve to suit their environment and to allow their bodies more access to the limited light. As a consequence, their skin and hair started to become much lighter. In the eastern steppes, however, things occurred slightly differently. A mutation occurred in a gene known as M1CR which caused hair color not merely to lighten but to change entirely- to red. The skin of these new redhead people was well adapted to absorbing the much-needed UV light. It was, however, a little too sensitive to the sun- which is why redheads often sunburn and are more prone to skin cancer. These pioneers of red hair then began to spread to the Balkans and central and Western Europe in the Bronze Age as they migrated once again, this time in search of metal. The majority of the migrants remained in these regions, although some spread further west to the Atlantic seaboard, and fewer still moved eastwards into Siberia and some as far south as India. However, these latter migrations were scant- which explains the rarity of red hair in these areas. The Balkans and Western Europe now became established as the geographical and historical homeland of red-haired culture. It was one that was observed by ancient writers who began to form their conclusions about the red-haired peoples they encountered. From the History Collection

11/7/2020 0 Comments The Mullet Story: a brief historya brief history This business-in-the-front, party-in-the-back style has been around way before it was popularized by actors and rock stars in the 1980’s. According to some historians, the mullet has been around since at least Ancient Greece, where the style was as much for function as it was for fashion. Cropped hair around the face with longer locks in the back allowed for both visibility and a protective layer of hair for your neck. Homer even described a haircut that sounds eerily familiar in The Iliad: “their forelocks cropped, hair grown long at the backs.”The Greeks weren’t the only ones sporting the mullet, though. There is evidence that Neanderthals and our oldest ancestors would wear this ‘do, as well. The relative ease of maintaining it makes it possible to keep up even without the existence of barbershops and hair salons, and the practicality makes it perhaps one of the oldest haircuts in human history.Some Native American tribes, both historically and more recently, have included the mullet with other traditional hairstyles. In many tribes, long hair is representative of a strong cultural identity. It is connected to values of family and community, and there are multiple rituals surrounding the upkeep of long hair. The preferred style for displaying long locks is most commonly braids – often two or three – but cuts closer the Mohawks and mullets have not been uncommon, either. Mullets have been present in and out through our entire history as a species, in different parts of the world. It wasn’t until the 1970’s when the mullet starting rising to modern mainstream fame, though, reaching its peak in the 80’s when everyone from George Clooney to Metallica’s James Hetfield sported one. It tended to be popular with white dudes who played rock music or hockey, incredibly cool and trendy for a while. The hairstyle didn’t actually have the name “mullet” until 1994, though, when the Beastie Boys released a song called “Mullet Head.” Not long after the name mullet was christened, the hairdo was on its way out. By the time the Beastie Boys gave the style its name, it had begun to slide from the trendy mainstream position it had been sitting comfortably at to a more countercultural phenomenon. The peak of mullets ended in the early 1990’s, but the style has never completely faded from relevance. Instead, it slipped from the good graces of the masses and became iconic in various subcultures: everyone from country music stars and lesbians, to hockey players and Native Americans. Jennifer Arnold even created a documentary about the haircut in 2002 titled American Mullet (which you can find on Amazon Prime if you’re curious). In more recent years, the mullet was actually banned in Iran, for being considered too much of a “western hairstyle”. No matter what you think of it, the mullet has become enough of a staple of the American aesthetic that it’s been placed in that categorization along with spiked hair, ponytails, and long hair in general. Will the mullet ever rise once more the its former glory in the 80’s? Maybe not, but it has certainly cemented itself as an iconic haircut from the past, and an important style to this day for many groups of people. Ten Iconic Mullets

The Mullet in 2020 It’s 2020, and the question everyone must now ask is: is the mullet coming back in style? Some may argue that it was never in style, while others will insist that it never went out of style. Ask the general public or a hair stylist, though, and they will probably be inclined to tell you that yes, the mullet is coming back. In January this year, men’s fashion blogs across the internet all declared the same thing: 2020 would be the year for the mullet. Beginning as a counter-culture hair style that was just getting its footing in the world of fashion once again, this year has proved to be the perfect time for the resurgence of the mullet. With hair salons being closed for multiple months in the first half of 2020, many people took on the dreaded task of facing down a home-brewed haircut. For some this manifested in a mullet style: either out of appreciation for the cut, or, perhaps, out of necessity. Get the hair off your face without worrying about trimming the back of your head where you can’t see. Like our ancestors before us, we must acknowledge the mullet for what it truly is: a practical haircut. The sudden lack of access to salons isn’t the only reason mullets are coming back, though. There have been whispers of the style in the mainstream over the last few years, and this was simply the boil-over point. In the second half of the past decade, we’d seen a steady increase of mullet action once again amongst the most famous of us. Ironically, a lot of the most notable celebrities actively rocking mullets today are women. Female singers especially. Everyone from Kesha and Miley Cyrus to Billy Eilish and even Zendaya have been seen sporting the look. What may have been considered a trashy style by many even just a few years ago has become a chic look sported by those of us who have a tendency to look coolest. When it comes to less famous women wearing the look, just as many have been sporting the ‘do as the pop stars and celebrities of the world. Especially amongst women in the LGBT+ community, the mullet is becoming as big of a fashion statement as it is amongst guys. Combine this cut with absurdly large earrings and colorful pants, and you’re ready to tell the world “Hello ladies! I, too, am gay.” Is the mullet resurging in popularity along with 80’s nostalgia-themed media, like It and Stranger Things? Perhaps. Like media and clothing, hair styles tend to move in cycles. Men’s hairstyles have been typically short-on-the-sides, longer-on-top for a while, now, and maybe the mullet is a shift out of those restrictions. Recent women’s fashion has involved a lot of things that were at one point, not long ago, considered tacky (looking at you, mom jeans and scrunchies). Maybe the mullet is the next step in this resurgence, allowing men to embrace the tackier sides of our previous societal fashion faux pas, as well. 10 Ways to Style Your Mullet

A female skeleton named Kata found at a Viking burial site in Varnhem, Sweden. Photograph: Vastergotlands Museum/PA They may have had a reputation for trade, braids and fearsome raids, but the Vikings were far from a single group of flaxen-haired, sea-faring Scandinavians. A genetic study of Viking-age human remains has not only confirmed that Vikings from different parts of Scandinavia set sail for different parts of the world, but has revealed that dark hair was more common among Vikings than Danes today. What’s more, while some were born Vikings, others adopted the culture – or perhaps had it thrust upon them. “Vikings were not restricted to blond Scandinavians,” said Prof Eske Willerslev, a co-author of the research from the University of Cambridge and the University of Copenhagen. Writing in the journal Nature, Willerslev and colleagues report how they sequenced the genomes of 442 humans who lived across Europe between about 2,400BC and 1,600AD, with the majority from the Viking age – a period that stretched from around 750AD to 1050AD. The study also drew on existing data from more than 1,000 ancient individuals from non-Viking times, and 3,855 people living today. Among their results the team found that from the iron age, southern European genes entered Denmark and then spread north, while – to a lesser extent – genes from Asia entered Sweden. “Vikings are, genetically, not purely Scandinavian,” said Willerslev. However, the team found Viking age Scandinavians were not a uniform population, but clustered into three main groups – a finding that suggests Vikings from different parts of Scandinavia did not mix very much. The team found these groups roughly map on to present-day Scandinavian countries, although Vikings from south-west Sweden were genetically similar to their peers in Denmark. Genetic diversity was greatest in coastal regions. Further analysis confirmed the long-standing view that most Vikings in England came from Denmark, as reflected in place names and historical records, while the Baltic region was dominated by Swedish Vikings, and Vikings from Norway ventured to Ireland, Iceland, Greenland and the Isle of Man. However, the team say remains from Russia revealed some Vikings from Denmark also travelled east. The study also revealed raids were likely a local affair: the team found four brothers and another relative died in Salme, Estonia, in about 750AD, in what is thought could have been a raid, with others in the party likely to have been from the same part of Sweden. In addition, the team found two individuals from Orkney, who were buried with Viking swords, had no Scandinavian genetic ancestry. “[Being a Viking] is not a pure ethnic phenomenon, it is a lifestyle that you can adopt whether you are non-Scandinavian or Scandinavian,” said Willerslev, adding that genetic influences from abroad both before and during the Viking age might help explain why genetic variants for dark hair were relatively common among Vikings. Dr Steve Ashby, an expert in Viking-age archaeology from the University of York said the study confirmed what had been suspected about movement and trade in the Viking age, but also brought fresh detail. “The evidence for gene flow with southern Europe and Asia is striking, and sits well with recent research that argues for large-scale connectivity in this period,” he said. “[The study] also provides new information about levels of contact and isolation within Scandinavia itself, and offers an interesting insight into the composition of raiding parties.” But Judith Jesch, professor of Viking studies at the University of Nottingham said the study is unlikely to rewrite the history books. “We long ago gave up on the most colourful popular myths about Vikings, and recent research has focused on the Viking age as a period of mobility, when people from Scandinavia migrated in various directions, and often back again, encountering and interacting with other peoples, languages and cultures in a process which I and others have called diaspora,” she said. Even so, Jesch said the study offered food for thought. “Archaeologists have long suggested that many cultural ideas reached Scandinavia through the Danish gateway, so it will be interesting to discuss further what this gene flow [from Denmark to Norway and Sweden] means in terms of how culture is diffused. Did it happen as a result of the movements of people or by some other process?,” she said. The article can be found here

|

Hair by BrianMy name is Brian and I help people confidently take on the world. CategoriesAll Advice Announcement Awards Balayage Barbering Beach Waves Beauty News Book Now Brazilian Treatment Clients Cool Facts COVID 19 Health COVID 19 Update Curlies EGift Card Films Follically Challenged Gossip Grooming Hair Care Haircolor Haircut Hair Facts Hair History Hair Loss Hair Styling Hair Tips Hair Tools Health Health And Safety Healthy Hair Highlights Holidays Humor Mens Hair Men's Long Hair Newsletter Ombre Policies Procedures Press Release Previous Blog Privacy Policy Product Knowledge Product Reviews Promotions Read Your Labels Recommendations Reviews Scalp Health Science Services Smoothing Treatments Social Media Summer Hair Tips Textured Hair Thinning Hair Travel Tips Trending Wellness Womens Hair Archives

April 2025

|

|

Hey...

Your Mom Called! Book today! |

Sunday: 11am-5pm

Monday: 11am-6pm Tuesday: 10am - 6pm Wednesday: 10am - 6pm Thursday: By Appointment Friday: By Appointment Saturday: By Appointment |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed